Tucson turns to native edibles for sustainability and resilience

The Watershed Management Group received an Arizona State Forestry Community Challenge Grant in 2023 to help fund the Native Edible Tree project, which focuses on native edible education.

Gracie Kayko / Arizona Sonoran News

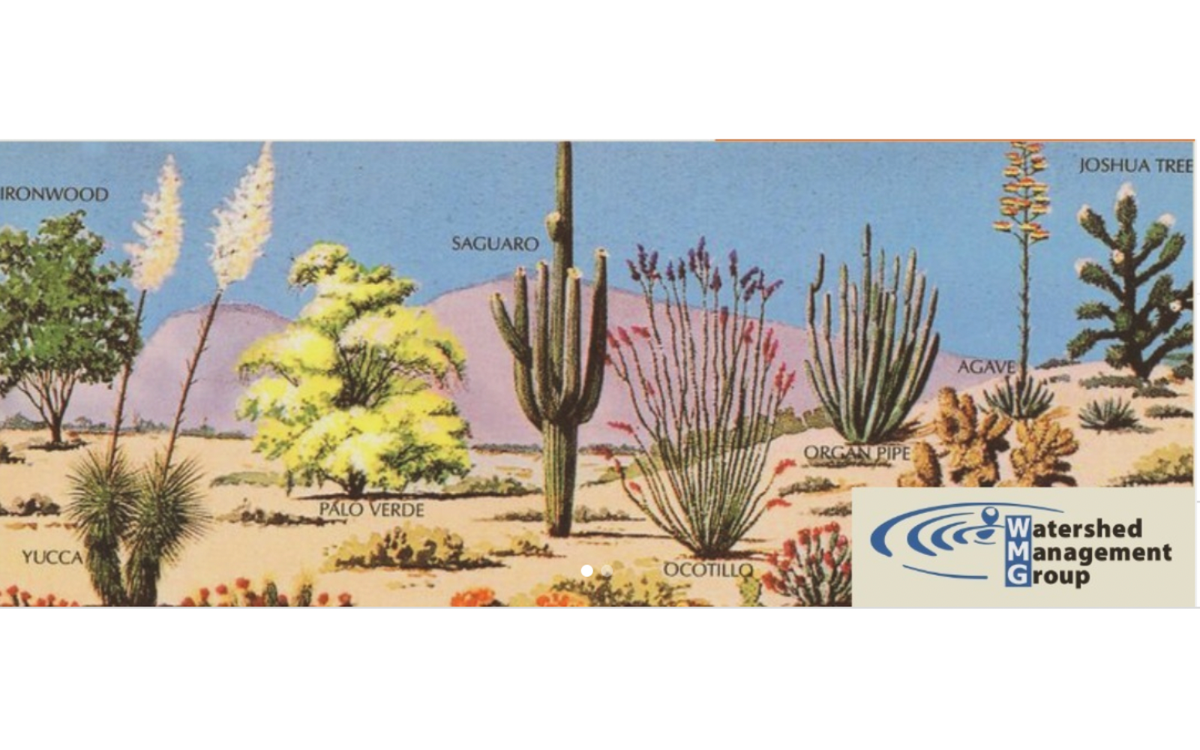

Located in the northern region of the Sonoran Desert and surrounded by five mountain ranges and 350 days of sunshine, Tucson is home to a thriving ecosystem of edible plants.

The saguaro, barrel and nopal cacti are native Sonoran Desert staples that are pictured on just about every postcard. They're also edible, as are ironwood, mesquite and palo verde trees, and flowers like globemallow and chuparosa.

These plants can teach us how to live in the desert, said Julie Regalado, education program director of Watershed Management Group.

Watershed Management Group is a nonprofit organization that works to educate the people of Tucson on how to live a sustainable lifestyle using local watersheds. The group’s mission is to “develop community-based solutions to ensure the long-term prosperity of people and health of the environment,” according to its website.

The organization received an Arizona State Forestry Community Challenge Grant in 2023 to help fund the Native Edible Tree project, which focuses on native edible education.

WMG educates the public about native edible foraging, cultivating, harvesting and processing of the plants to help people understand their relationship to the Sonoran Desert land and waterways.

One of the goals of the Native Edible Tree project is to look at the possibility of reestablishing the ecosystems in which native edible plants grow, Regalado said.

“While we recognize that people probably won’t convert to making those native edible species the main part of their diet, we think that when they recognize and appreciate that they’re everywhere here, then they begin to reframe their relationship with the Sonoran Desert and perhaps have more appreciation and understanding of all that it offers,” Regalado said.

Tucson was named the first UNESCO U.S. City of Gastronomy in 2015, but is still considered a food desert in many areas.

But native edible education, Regalado points out, can help alleviate the anxiety people may have while living in a food desert. The food is there and can be used the way Indigenous people of the land have been using it for thousands of years.

Manuel Barcelo, an intern with the Native Edible Tree project, explains how native edible trees can replace store bought, processed snacks in someone’s diet.

“I think (native edibles) won’t completely solve the issue (food insecurity,) but it’ll give people an opportunity or option when it comes to getting food and replacing snacks,” he said. “If it replaces a kid eating chips once a day and just snacking on some fruit, that’s positive.”

Charles Rodgers, owner of Earthcare Landscapes and co-owner of Sonora Flora Nursery, views native edible plants as a solution to food insecurity and waste.

Native edible plants "grow here inherently and they are food producing at the same time,” Rodgers said.

And when it comes to food waste with native edibles, whatever humans don’t eat, the birds will, he added.

Foraging native edible plants out in nature takes time and practice, but it gives humans a deeper connection to the environment around them than other outdoor activities such as hiking, biking and running, said herbalist John Slattery.

With outdoor physical activities, a person is passing through nature, but with foraging, they're really connecting with it.

“The benefits to us are being engaged with the natural world, observing the seasons, and having some sort of active, even productive, relationship with the natural world,” Slattery said.

Natural benefits of native edible plants

Native edible trees and plants have a bounty of benefits to the desert and the people living in it. The trees and plants native to the Sonoran Desert are accustomed to living in the dry, and sometimes unbearable, heat and require less water than non-native species.

Tucson gets its water supply from the Colorado River, along with seven other states and Mexico. According to Sustainable Tucson, in 2023, there was a severe water shortage due to over-pumping of the river, climate change and drought, causing the Colorado River to deplete.

But native edible plants rely on Tucson’s two monsoon seasons for their water supply, requiring less supplemental water than non-native plants.

Regalado said she admires the work being done by the San Xavier Co-Op Farm to plant taparia beans and watermelons during Tucson's hot summer temperatures.

“They plant them when it’s hot and the seeds wait, and when the monsoons come, they grow,” Regalado said.

Most native edible trees only need supplemental water for the first one to two years after being planted. After that, when they’re established, they are able to live, grow and flourish on their own.

The mesquite tree, for example, is a native tree that produces edible pods on its branches. It needs to be watered for the first one to two years to become established, and after that, it’ll adapt to only using water when the monsoons come.

The pods from the mesquite tree are harvestable in June when the beans inside make a rattling sound when shaken. The mesquite beans from the pod have a sweet flavor, but the typical way of consuming them is by making mesquite flour or broth.

These plants also provide shade to humans and habitats to critters.

Watershed Management Group started the “Cool Our Cities 5 Degrees” mission in 2023 to help reduce the growing heat island effect caused by the pavement of roads and parking lots, buildings and more.

According to the EPA, the heat island effect in the United States boosts temperatures in urban areas about 1–7 degrees during the day, 2–5 degrees at night, according to the group’s fall 2023 newsletter written by Executive Director Lisa Shipek.

The expansion of the city has contributed to an additional 5-7 degrees heat in Tucson.

Promoting native edible trees and rain gardens is one of the ways Tucson can bring down the heat, because the trees provide shade.

“We think it’s a way to contribute both to beautifying our city, making the city more walkable by providing shade, and bringing the temperatures of the city down,” Regalado said.

When native edible plants are planted together throughout neighborhoods and the city, it becomes a habitat for native wildlife.

Tucson is home to an array of native bees, but because of the introduction of non-native bees and plants, the bees are losing their environment.

“Wildlife knows how to find the ecosystems that work for them; it’s survival for them,” Regalado said.

Planting more native plants will give the wildlife back their home.

“A lot of the insects and birds and wildlife actually rely on cities now because so much of the wild space has been taken over,” Rogers said. “The more you plant the better it is to sustain the web of life actually in the urban environment.”

Building landscapes for native edible trees and plants throughout the cities can also help minimize flooding during heavy monsoon rains.

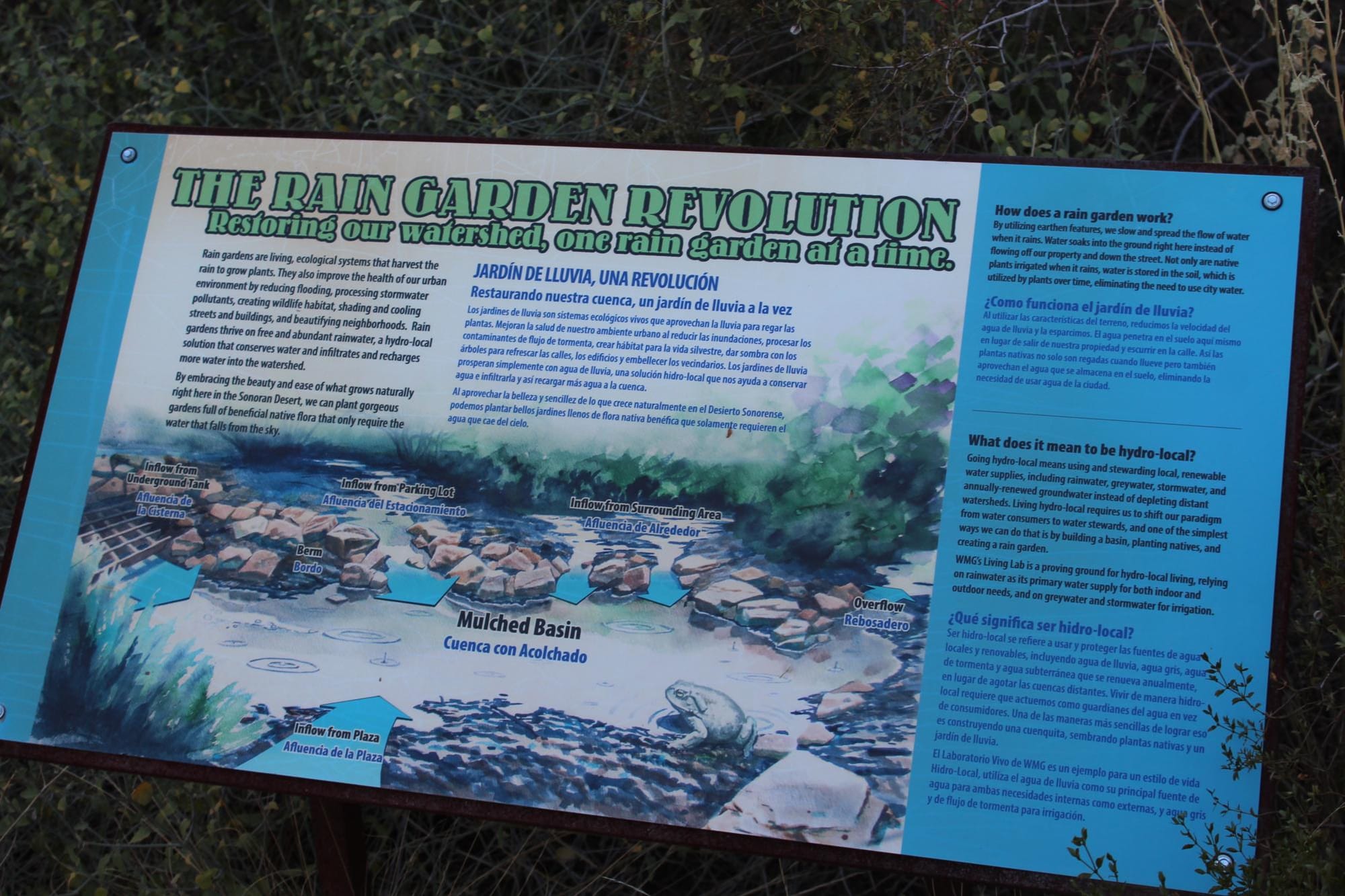

Rain gardens help edible plants thrive

Rain gardens reduce flooding, produce shade and provide a habitat for animals and insects and help deter flooding.

“Once you build the environment for them to succeed, like the rain gardens, it’s really cool seeing how lush they can get and there’s no supplemental water,” said the Native Edible Tree project's Barcelo.

WMG held rain garden workshops at their "Living Lab" at at 1137 North Dodge Boulevard with money from the grant. Barcelo said one of the workshops' most impactful lessons was the thermometer activity, where he showed participants the difference in temperature between a surface in the sun and a surface under shade from a native edible tree.

“People are always surprised to see how much lower the heat is in shaded areas,” he said.

During a Native Edible Tree project event on Nov. 13, participants were taken on a tour of the demonstration site to see the group’s rain gardens. Regalado explained how the rain gardens are built, where different native edible plants should be planted and how they differ across the areas of the property.

The rain garden resembles a basin, with the center of the garden being significantly deeper than the outer edges with a 33 degree angle to the center. According to WMG, cactus and native edible trees should be planted along the basin slope, while grasses are grown in the deepest part of the basins.

The optimal time for planting rain gardens are March and April, and again in mid-September to November, due to the desert’s low heat and chances of frost.

Although the grant and Native Edible Tree project is coming to a close, Watershed Management Group will always be promoting awareness about the use of native edible plants in the Sonoran Desert through their Living Lab, demonstration site and Cultivating Native Edible class. The classes are part of the Hydrate series and are offered two to three times a year.

For more information on rain gardens, visit watershedmg.org.

Arizona Sonoran News is a news service of the University of Arizona School of Journalism.