Assistance is available to Pima County voters with disabilities - if they ask

In 2022, 14% of voters with disabilities reported some kind of difficulty casting a ballot, more than any other group and amidst expanded access to mail-in voting during the pandemic.

Early voting has been the standard for decades, and while it aims to simplify the process, for some voters that’s simply not the case.

In 2022, 14% of voters with disabilities reported some kind of difficulty casting a ballot, more than any other group and amidst expanded access to mail-in voting during the pandemic, according to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission.

That’s an increase of 3% from 2020. And it meant that the likelihood of a disabled voter encountering a challenge was significantly higher than a non-disabled voter — 20% to 6%, respectively.

The Center for Disease Control reports that more than one in four American adults has a disability. And while there have been significant efforts in recent years to increase voter accessibility, much of the work has focused on creating additional polling places and early voting sites.

This leaves voters with disabilities looking for answers about how they can ensure their vote is secure, the kinds of accommodations they are legally entitled to and their availability.

These accommodations include service animal support, handrails on stairs at voting locations, accessible parking, large-print voting and election materials, wheelchair-accessible voting centers and at least one accessible voting device at every location for voters who are blind or visually impaired.

The accommodations also include assistance while voting, either in the form of poll workers to help with the accessible voting devices, or a person other than an employer or union representative who can assist with filling out a ballot.

But even with the laws, not every voting location is accessible to every voter, meaning that for disabled voters, it’s rarely a simple process.

Jean Parker, founding executive director of the Colorado Cross-Disability Coalition, has been grappling with the challenges of voting as a visually impaired person for years, and was finally able to vote privately for the first time in 2022.

“All the times prior to that, I had some assistance,” she told Tucson Spotlight.

Parker moved to Tucson during the pandemic but didn’t know what kind of accommodations were available through the Pima County Recorder’s Office in time for the 2020 election.

“I had to have someone fill out my ballot and took a chance that they filled it out correctly,” she said. ”I didn’t know Pima County had the machines and apparently have had for a number of years until I joined the (Arizona chapter of the National Federation of the Blind)., It’s like a secret that you have to know the right people at the right time to know.”

And while the devices are good for early voting, Parker said, they’re far from perfect and they pose some potential challenges for visually impaired voters who wait until Election Day to cast their ballot.

With a single device at each polling place, voters run the risk that it might not work or that none of the poll workers know how to use it.

“I would be really stressed out if I had to wait for Election Day to go to the polls and wait in line to find out the machine isn’t working, and that happens to people,” she said. “And that’s where disenfranchisement comes in. All the factors that have to line up for someone to cast a private, accessible vote.”

Disabled voters have to consider factors other voters do not, and under the current system, this isn’t an equal process, Parker said.

“So much of the time the definition of voter suppression is based on race or income or rural location or languages, but no one ever talks about this,” she said.

But it doesn’t have to be this way, Parker said, pointing to years-long efforts by chapters of the National Federation of the Blind to bolster support for legislation to address the issue.

Parker said that one solution could be to adopt an online voting system for people with a disability, much like the one used by domestic voters living overseas.

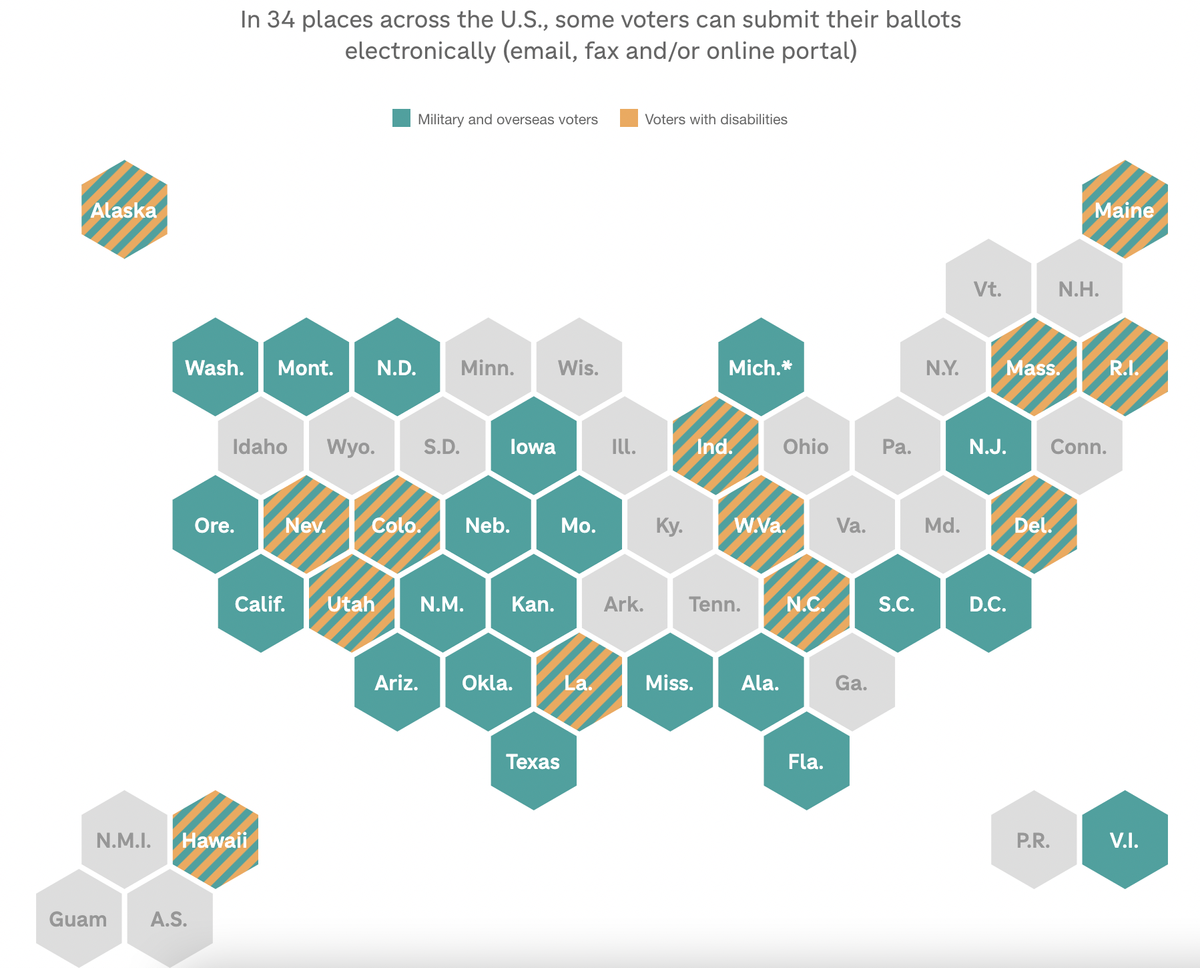

Electronic ballot return is already available in 34 places in the United States, either through email, fax or an online portal, according to NPR, who reported that in 2020, more than 300,000 Americans voted via one of these means.

But like most things election-related, every state does it differently. Thirteen states allow voters with disabilities to vote electronically, but Arizona isn’t one of them, even though it allows electronic return by members of the military and overseas voters.

“There are also other systems, like what Colorado has instituted. They passed a bill, and many other states have passed bills to fix this,” Parker said. “But Arizona doesn’t seem to be able to do this, even though the fix to this is readily available and reachable and doesn’t involve a large appropriation.”

All of this points to the larger problem of the lack of continuity in voting procedures across the country and even within individual states, as a result of letting individual jurisdictions determine their own processes.

“It’s very ambiguous how this is set up,” Parker said. “This is how it works in Pima County, but if you’re in Sierra Vista say, or somewhere in Cochise County, who knows what happens.”

The Pima County Democratic Party sent out an email to subscribers last week reminding them of accessible voting options and advising they contact the recorder’s office before Election Day to confirm that accessibility accommodations are available at their preferred voting location.

“When you talk to them, be clear about what you need to make voting easy for you,” the email said. “If you learn that your voting location is not accessible to you, ask your election office about other available options.”

The email reminded recipients of the five federal laws protecting the registration and voting rights of people with disabilities and advising anyone who believes they were discriminated against due to disability to report their experience to the Department of Justice.

While Parker said she appreciates the ability to vote through the accessible devices, she’d like to see more outreach by the recorder’s office to let visually impaired voters know they exist.

She’d also like to see the process made easier for disabled voters, either through the introduction of federally mandated, uniform procedures that allow for online voting, or through other means. Regardless, she said, the system as it exists in Arizona is not equitable and needs to change.

“When I go to vote, I call up our contact at recorder’s office, which is not someone who is publicly designated as person to call, and I say, ‘I am going to voting thing today at this time and my expectation is that the machine will be available, working and staff will know how to manage this,’” Parker said. “Most people aren’t going to do that. Most people will say, ‘Screw it. I won’t vote or I’ll have someone fill out my ballot and take my chances,’ or some other more passive response. But they likely won’t vote.”

Caitlin Schmidt is Editor and Publisher of Tucson Spotlight. Contact her at caitlin@tucsonspotlight.org.

Tucson Spotlight is a community-based newsroom that provides paid opportunities for students and rising journalists in Southern Arizona. Please support our work with a paid subscription.