Local experts discuss impact to children of parental incarceration

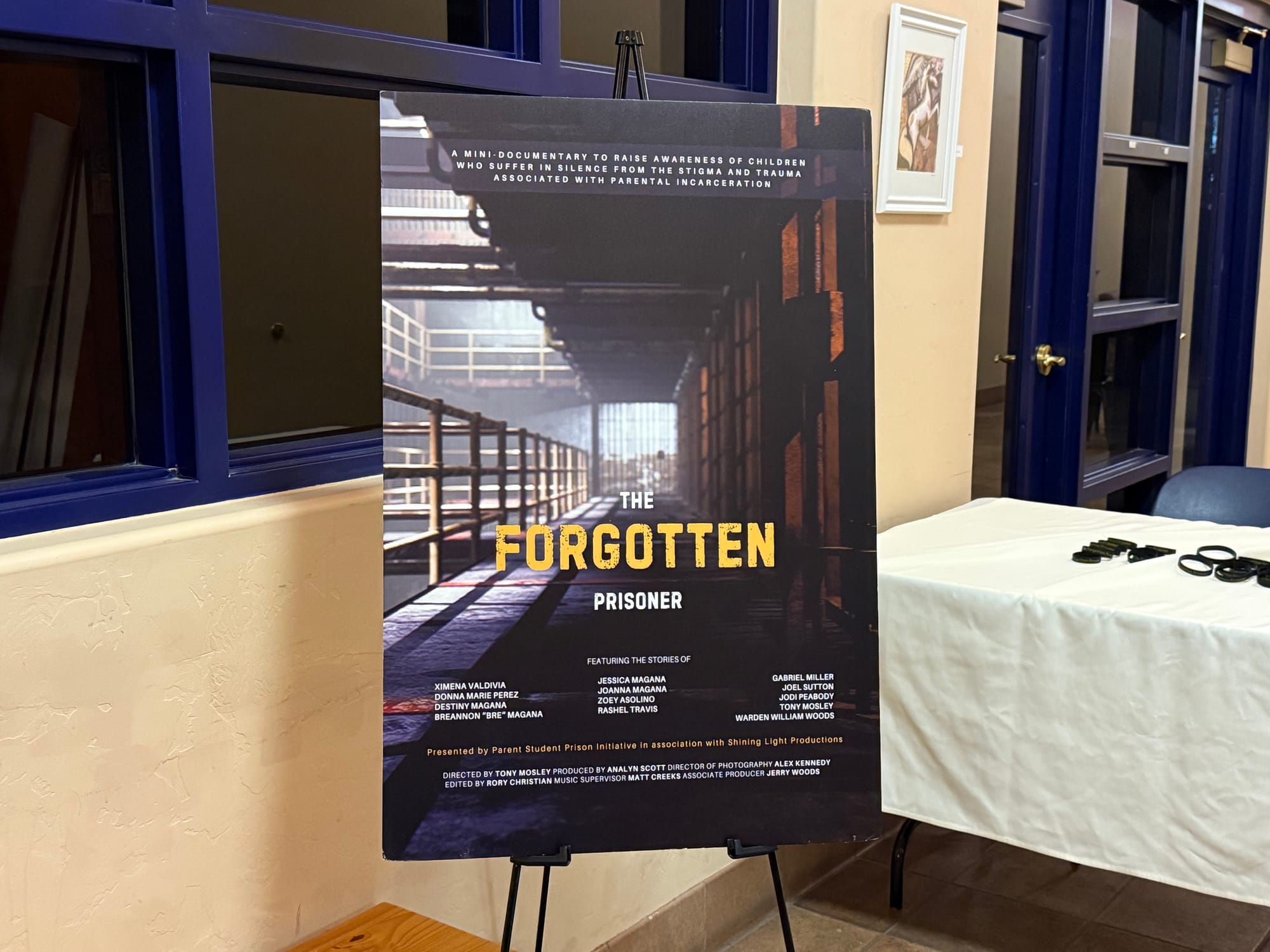

More than 2.7 million children in the U.S. have an incarcerated parent. A panel of local experts discussed the impact of incarceration on families, following a Saturday screening of the mini-documentary "The Forgotten Prisoner."

One in 28 kids in the United States has a parent serving time in prison or jail, with that separation leading to challenges for their children.

A panel of local experts discussed the impact of incarceration on families, following a Saturday screening of the mini-documentary The Forgotten Prisoner, which highlights the emotional and social struggles of children who are separated from a parent by prison walls.

Dozens of community members gathered at the YWCA of Southern Arizona to watch the film and hear from the panel, which included:

- Charlinda Haudley, an outreach coordinator for the Central Arizona Project

- Amber Santa Cruz, a behavioral health therapist specializing in Native American women and families

- Doyle Morrison, program manager for Pima County’s Transition Center

- Bruce Donahue, a justice navigator at the center

- Tony Mosley, the film’s director.

The panel was moderated by Larry Starks, a retired correctional administrator with over 35 years of experience working with at-risk youth.

More than 2.7 million children in the U.S. have an incarcerated parent. The documentary follows several children impacted by parental incarceration, offering an inside look at lives.

“We really want to work together to provide a conversation to say, ‘How do we support this particular demographic of kids?’” said Mosley, who is also working on a project that brings nonprofits together to discuss what’s working and how they can better serve these children.

Haudley shared her experience when her father was incarcerated in 2019 while she was in her Ph.D. program.

“It was really difficult because I wanted to quit,” she said. “I didn’t know who to talk to or what resources were available to me.”

Raised on the Navajo Nation, Haudley struggled with how to care for herself spiritually and culturally after her father’s imprisonment, as she didn’t have access to traditional ceremonies.

Instead, she found support in the running community, using it as a tool for emotional processing and healing.

“Having those conversations about going for a run and making sure that you process this and journal about it is important,” she said. “Think about how this is impacting you and really encouraging that healing process for individuals.”

Pima County’s Morrison, a father of four who was previously incarcerated, spoke candidly about the long road to rebuilding trust with his kids.

“It was very difficult because I had betrayed their trust,” he said. “When I got home, I had to rebuild that trust and reestablish those relationships.”

Now adults, his children still face the consequences of his criminal record, wondering if it will hinder their own opportunities.

Donahue, a member of the Tohono O’odham Nation, highlighted the role of culture and community in helping his children cope with his incarceration.

“It was the aunties and uncles that reached out to my children and took them to ceremonies,” he said.

Donahue spoke about a community event designed to teach young boys whose fathers were incarcerated about traditional games and language, providing a cultural foundation that helped prevent them from entering the criminal justice system.

“It was there that it was instilled in my children that culture was going to be part of the prevention,” he said.

Behavioral health therapist Santa Cruz talked about the long-term consequences of childhood trauma, particularly in Indigenous and minority communities. Children facing adversity are more susceptible to health disparities, including substance use, mental health issues, and chronic conditions like high blood pressure and diabetes.

“The question is, how are we serving these youth and breaking the cycles?” she asked.

Santa Cruz suggested that schools increase counseling services and provide families with psychoeducation to help them cope with the stress of having an incarcerated parent. She also noted that the remaining parent often becomes the sole provider and struggles to meet both financial and emotional needs.

“In thinking about how we can help heal these children, we have to think about the family unit as well,” she said. “What are the symptoms, and how can we get to the root causes to make a change?”

Morrison said community outreach programs, especially those run by churches, can play a vital role in supporting children of incarcerated parents, but it’s not always a simple process.

“The biggest (challenge) would be identifying those families in your community — children being raised by grandparents because parents are dealing with substance abuse, mental health issues, or are incarcerated,” he said. “Kids aren’t going to tell you my dad is locked up. They suffer in silence.”

For many children, the road to healing begins with building trust and providing emotional support.

“We have to be open and talk to our kids and talk to our family members and address what's going on in our families,” Starks, the moderator, said. “We have to support each other.”

Isabela Gamez is a University of Arizona alum and Tucson Spotlight reporter. Contact her at gamezi@arizona.edu.

Tucson Spotlight is a community-based newsroom that provides paid opportunities for students and rising journalists in Southern Arizona. Please support our work with a paid subscription.