“Fear turns into power”: How one Tucson couple is preparing for Trump’s second term

One Tucson couple is fighting for the rights of undocumented community members, but they themselves are also undocumented, adding uncertainty about Trump's promises of mass deportations.

As Donald Trump’s inauguration day nears, communities across the United States are bracing themselves for the impact of his second term.

Trump repeatedly rolled back protections for women and the LGBTQ+ community during his first term, and he said during his campaign that he’ll enact the largest mass deportation effort in U.S. history.

Many of these communities fear attacks on their rights, but for people whose identities intersect communities, that fear is intensified.

“I have three things against me: I’m a female, I'm gay, I'm brown,” Elsa told Tucson Spotlight. “So I have a lot of struggles, but I've never given up on life, even if I have had really dark moments.”

Elsa is an organizer with Coalición de Derechos Humanos, a grassroots organization that promotes human and civil rights of all migrants, regardless of their immigration status.

Her partner, Luna, is also an organizer, with the two playing a significant role in helping immigrants prepare for Trump’s return to office.

In Arizona, immigrant communities are also fearful of the possibility of additional deportation threats under Proposition 314. While some provisions of the new law have already been enacted, two are waiting on a ruling in Texas over a similar law, SB4.

Prop 314 has been called a repeat of SB 1070, the infamous “Show Me Your Papers” law passed in 2010. If found Constitutional, Prop 314 would allow for law enforcement to act as immigration officers.

This new threat has caused immigrant rights organizations to mobilize.

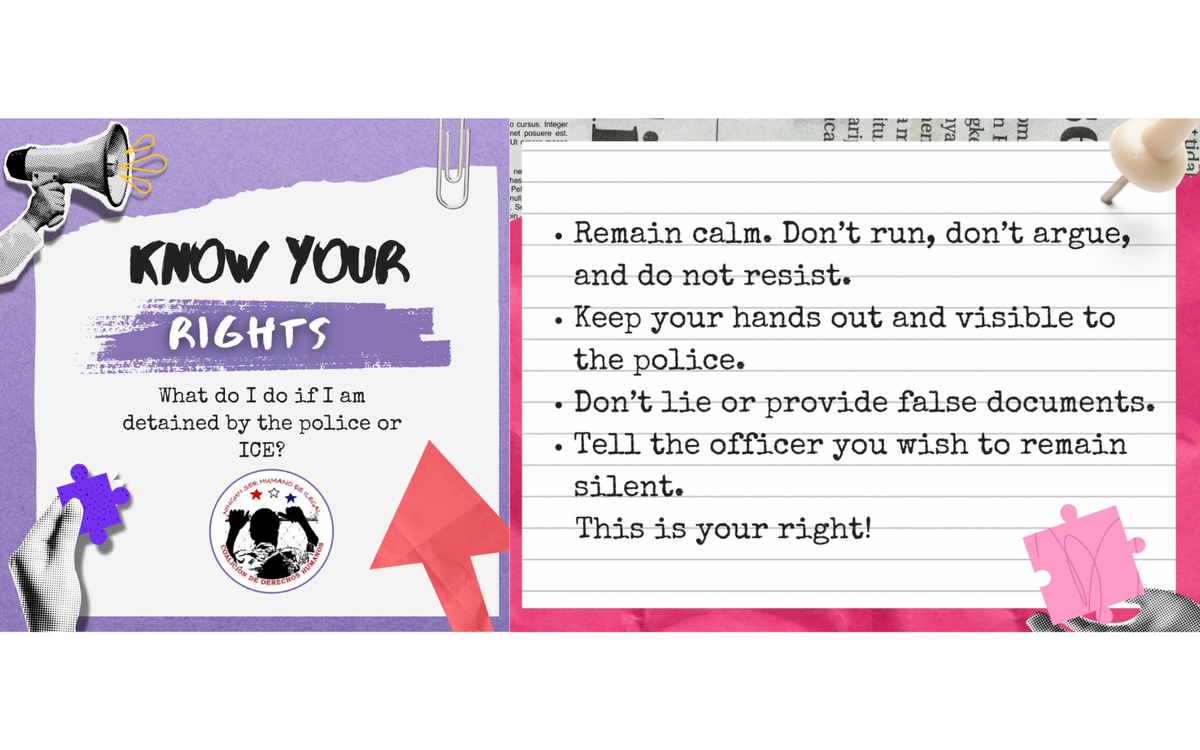

Derechos Humanos held a Know Your Rights session in December in response to the passing of Prop 314, at which they distributed a guide for people fearful of deportation, created by Luna and Elsa. It included information about where to store important documents, how to financially prepare and how to handle child care.

“At some point I stepped back from the laptop and I was like, ‘Oh my God, all this was in my head.’ It's like second nature at this point,” Luna said. “I know what to do, I know what to ask for, I know everything. That’s so messed up.”

A recent UnidosUS poll showed that Latino voters prioritize relief for long-residing undocumented people, not mass deportations. Many Latinos have advocated for immigration reform and a pathway to citizenship for decades.

While Luna and Elsa are fighting for the rights of undocumented members of the community, they themselves are also undocumented, adding another layer of uncertainty about the Trump administration’s promises.

Out of respect for Luna and Elsa's situation, Tucson Spotlight is not publishing their last names.

“We weren’t anything”

Luna was born in Monterrey, Mexico, and crossed into the United States with her mother and younger brother when she was only 4, following her father to Dallas.

She was taught to make herself invisible for the protection of herself and her family.

“You can be all these amazing, great things, but because of that, if somebody finds out, you'll be in danger and then you put your family in danger. And all these things will be taken away from you,” she said. “And so the fear just accumulates to the point where I'll just follow the rules and just stay quiet.”

Luna says that Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals saved her. The immigration policy allows for certain people who came to the U.S. as children to live and work without fear of deportation.

“I was 17, about to turn 18, and the day that you turn 18 counts as your first illegal day here,” Luna said. “I got (DACA) and then two weeks later, I turned 18. I got it right in the nick of time.”

She was later told never to let her DACA status expire and that, “the day you let it expire, you automatically consent to be here illegally.”

DACA status needs to be renewed every two years. The process requires a fee of $500-600, fingerprinting, producing tax documents and proving model citizenship.

The earliest day Luna can renew her DACA status this time around is in April, and she fears that she won’t be able to do so under the Trump administration.

She’s also afraid that the information she willingly provided the government will be used against her and her family members, who have lived in the shadows for over two decades to avoid deportation.

“We didn't go to organizations. We weren’t part of the community. We weren't with anything,” she said. “It was more like, stay inside the house only going from school and then come back or work and come back.”

“There’s nothing back in Mexico for me”

While Luna was taught to be quiet and reserved, Elsa's unapologetic and rebellious attitude helped her find her voice and community.

Elsa was born in Colima, Mexico, a state nestled between Michoacan and Jalisco. She crossed the border into the U.S. with her mother when she was very young and doesn’t remember much about the journey, only recalling how the adults around her made it feel like an adventure.

“From what my mom told me, it was pretty scary for adults,” she said. “But I guess as a child you don't really perceive the dangers of it.”

While the move was for a better quality of life, it didn’t turn out to be exactly the American Dream.

Elsa describes herself as a “broken child,” growing up in a neglected home. She hung with the wrong crowd and committed petty crimes. When she turned 21, her mother sent her back to Colima, where she suffered sexual abuse and a months-long kidnapping.

“Colima was rough… I suffered a lot during that time,” she said.

After three years, her mother helped Elsa return to the U.S. with a U Visa, a visa for victims of certain crimes who have suffered mental or physical abuse and help law enforcement or government officials in the investigation or prosecution of criminal activity.

After she returned, Elsa enrolled in nursing school, where she discovered a deep passion for helping others. But her studies were cut short a semester before graduation, when her lawyer advised her to move closer to the border, anticipating developments in her case that would require her presence in court.

While still in the process of fixing her citizenship status, she was arrested for a DUI, and her immigration lawyer was no longer able to help her, as her case now included a criminal charge.

She paid $5,000 out of pocket to hire a new lawyer, who she said took her money and mismanaged her case. She then took her case to another lawyer in Phoenix, but the same thing happened again.

Immigration fraud is a common occurrence within the undocumented community, and filing incorrect paperwork can cause government investigations and trigger deportation proceedings.

There are many online resources to help immigrants find the right lawyer and consultants, but many people are still scammed by fake lawyers and blown off by the legitimate attorneys they hire.

Elsa said she lost a lot during this time.

“It was really another really sad moment in my life where I was like, ‘I'm giving up. I'm so done with this,’” she said. “In my mind I was already going to go back to Mexico. But honestly, there's nothing back in Mexico for me.”

Elsa still lives in a state of limbo, not exactly undocumented, but not documented either, which has restricted her ability to live a full life. With her current status, she can’t rent an apartment, buy a house, purchase a car or get a driver's license, among other things.

But she still finds solace in the work she does.

“Fear turns into power, and if you are in the right community, if you know the right people, that fear can turn you also into something completely opposite,” Elsa said.

“We still have each other”

Luna and Elsa found each other on a dating app.

The two had always been told to look for a relationship with people with papers or citizenship and they remember the conversations they had while trying to figure out the other’s status.

“It turned out that we're both in this situation where we can't help each other,” Luna said.

But they gained something else in their relationship: A true understanding of what the other is going through and a solidarity that can’t be found anywhere else.

Luna drove from Dallas to pick Elsa up in Tucson, after the latter had a fight with her mother, arriving at her doorstep at 3 a.m.

It was on the trip back to Texas that they both knew they'd found the support they needed, after so many years of living in fear.

After living in Dallas for some time, they moved back to Tucson, where Elsa felt more at home and connected with the community. It was then that she ended up getting involved with PANTERAS, an Amphi tenant activist group, and eventually with Derechos Humanos. She also introduced Luna to the groups.

The two were reeling the day after the election, when they found out that Trump would once again be president.

But that only lasted a moment before they started organizing and using their voice to spread awareness about the rights of people without legal status.

They helped organize December’s Know Your Rights meeting, during which dozens of community members showed up to learn about resources.

“There are so many people who, like me, didn't believe in (our power), who think their voice will never be heard,” Elsa said. “Me being bilingual gives me that little bit of a head start, because it's also important to be able to communicate with these people in English and Spanish and all the languages that we can. I wish I could speak all of them so I could talk to everybody.”

The couple have decided they will no longer let fear control them.

“I'm scared, but how much more can I live in fear until I realize that it's enough?” Luna said, adding that if she’s deported, the U.S. will be losing an asset.

Immigrants, documented and undocumented, drive prosperity and innovation, are beneficial for the economy and fill critical jobs across the country. They’ve also helped keep programs like Medicaid and Social Security afloat, thanks to the millions they pay in taxes, despite their chance of never being able to reap any of the benefits offered by those programs.

Researchers say that if Trump makes good on his promise and carries out the largest deportation effort in history, the impact to the economy could be detrimental.

Both women have now lived in the United States longer than they’d lived in Mexico and have built lives in this country. Luna works for an insurance agent for travelers and Elsa has a job as a caretaker.

“If shit does hit the fan, we still have each other,” Elsa said. “If I get deported or she gets deported or anything like that, at the end of the day, I know that I can trust her. I can trust the fact that I'm not going to be left all by myself out there.”

But that doesn’t quell Elsa's fears about Winston, a 3-year-old chihuahua and Elly, a 4-month-old Maltese mix. She wants to make sure they’re taken care of, should anything happen to her.

Luna has worries of her own, but she’s made peace with the potential for deportation..

“I'm at the age where I'm like, you know what? I've experienced the United States, it's been great. But if you choose to make me go, I'm okay. I won't be mad,” Luna said. “Just let me know, because I’ve got to advise my job.”

Susan Barnett is Deputy Editor of Tucson Spotlight and a graduate student at the University of Arizona. She previously worked for La Estrella de Tucson. Contact her at susan@tucsonspotlight.org.

Tucson Spotlight is a community-based newsroom that provides paid opportunities for students and rising journalists in Southern Arizona. Please support our work with a paid subscription.