From DNA to space: SARSEF projects shaped by the scientific boom

SARSEF's early years in the 1950s and ’60s showcased student projects inspired by breakthroughs in DNA research, space exploration, and environmental science.

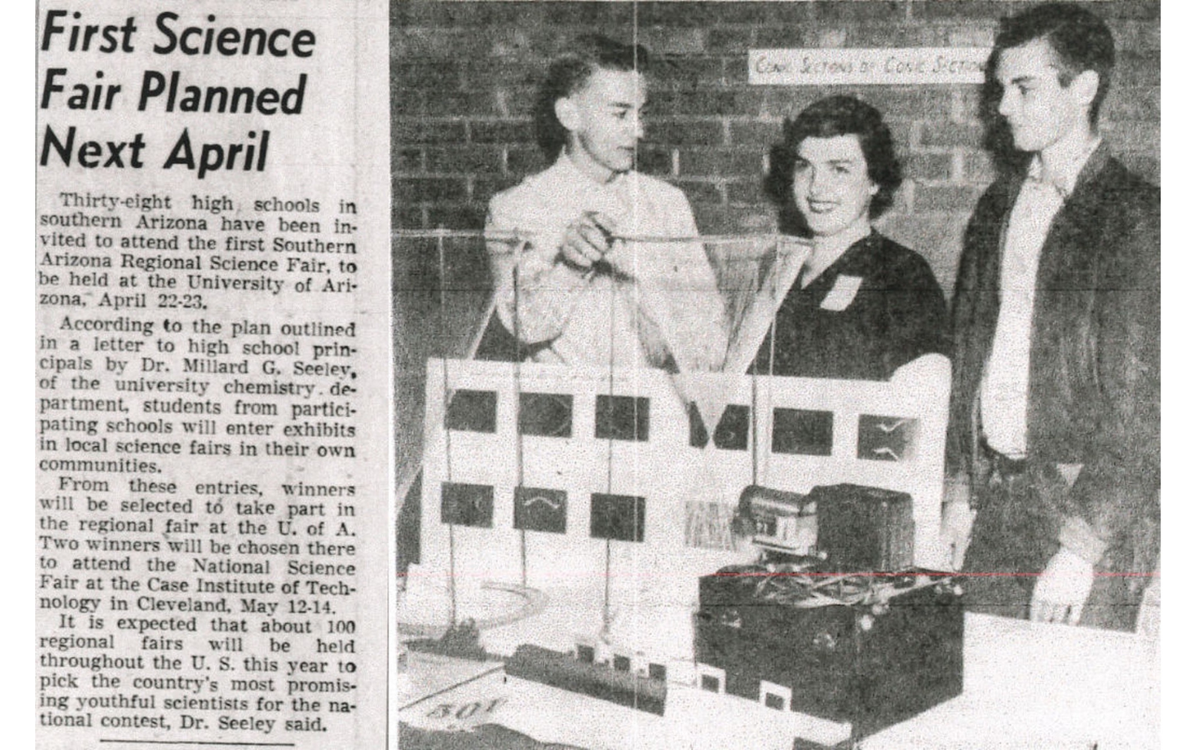

Founded in 1955, the Southern Arizona Research, Science, and Engineering Fair quickly became a platform for young scientific minds across Southern Arizona.

The first fair featured 120 projects, with two advancing to the National Science Fair. The inaugural event set the stage for what would become a cornerstone of scientific curiosity and academic excellence in the region.

Over its 70 years, entries in the fair have largely mirrored the global scientific discourse of the times, so Tucson Spotlight is taking a trip back into the past and diving into the history of SARSEF’s science fairs.

In its first year, two standout projects — Richard Sommerfield’s “A Study of Conic Sections” and John Bonecutter’s “Ozone Generator” — advanced to the prestigious International Science and Engineering Fair. Those projects focused on mathematics and environmental science, and explored the growing understanding of the ozone layer and the rapid advancements in environmental research.

Sommerfield’s project tapped into the emerging use of advanced mathematical models to explain natural phenomena, a concept that was gaining momentum as part of the broader push toward computational science and space exploration.

Bonecutter’s “Ozone Generator” reflected growing concerns about the effects of industrialization on the atmosphere; concerns that would grow in prominence over the next several decades.

The fair’s early success was marked by the support of local organizations. The American Chemical Society, which awarded Monte Nichols $25 for his crystal growth project, while the Tucson Pharmaceutical Association provided a double scale graduated flask to Elizabeth Boyle, who studied Vitamin A deficiency in mice.

These prizes demonstrated the community's investment in nurturing young scientific talent and the importance of hands-on learning, which was becoming a hallmark of educational reforms in the post-war era as more emphasis was placed on creativity and problem-solving skills in students.

By 1958, SARSEF had become a key fixture in Southern Arizona's educational landscape. Ann Lyon and Richard Jensen's selection to attend the International Science and Engineering Fair in Flint, Michigan marked a significant milestone for the fair.

Their projects, along with others from that year, reflected the scientific discovery of the era: DNA.

Sylvia Kerr’s research on the “DNA Chemical Basis of Genes” was likely inspired by the groundbreaking discovery of the DNA double helix in 1953, which sparked widespread interest in genetics and biology.

Other notable projects included studies on extinct species like the Columbian mammoth, the Van de Graaff machine, and the importance of the solar system. There was even a project tracking the medical history of an injured horse.

These projects echoed the rapid scientific advances of the 1950s, a decade defined by discoveries that revolutionized biological sciences. At the same time, the booming field of paleontology, driven by fossil discoveries, inspired students to explore ancient life forms.

The 1950s also saw students submit projects that directly correlated to the era’s scientific priorities, such as space exploration and practical engineering. In 1959, projects like “Plant Life on Venus” showcased students' growing interest in space.

These topics paralleled the international race to explore space, particularly after the Soviet Union’s successful launch of Sputnik, the first artificial satellite, in 1957. It also reflected the increasing attention being paid to astrophysics and astronomy, fields that were gaining in popularity and importance as space exploration became a focus of Cold War rivalry.

Other projects, like “Electrical System of a Car” reflected a practical engineering mindset and were inspired by the post-WWII economic boom. After the war, America was rapidly becoming a consumer-driven society, with the automobile industry expanding and a growing interest in technological innovations for the home and industry. These projects also reflected the increasing trend toward applied science that directly impacted everyday life.

The ushering in of the 1960s saw increased participation and academic enthusiasm for science, with schools across Southern Arizona becoming more involved in SARSEF.

Notable Tucson philanthropist Sam Hughes won an award for his project in 1963, one of the 250 projects that were submitted by his school. This surge in interest was linked to the national focus on science and technology during the Space Race. In response, American schools began placing a stronger emphasis on STEM subjects.

Books like “You, Your Child, and Science,” which encouraged parents to engage their children’s scientific curiosity, were gaining popularity. The increased interest in science education at home helped to fuel the next generation of scientists.

In 1962 and 1963, SARSEF continued to feature projects that showcased both innovation and scientific rigor. Some of the notable entries included Sondra Kay Johnson, a senior at Rincon High School who suffered from severe allergies and decided to study pollen, and Gary Walker’s model of a wheeless car, powered by a self-generated stream of air.

These projects, while grounded in biological and physical sciences, also reflected the rising interest in environmentalism and alternative technologies during the 1960s. The counterculture movement and the early days of green energy were beginning to influence public thought, encouraging projects that reimagined the future of transportation and sustainability.

The cultural climate of the 1960s also influenced the types of projects featured at SARSEF. The social movements of the time — such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed discrimination, and the Stonewall Riots of 1969, which sparked the LGBTQ+ rights movement were beginning to shape young people's awareness of the world and their scientific pursuits. These movements encouraged young people to question established norms, leading them to explore new, sometimes unconventional areas of research.

The 1960s were a time of social change, technological advances, and heightened awareness of global issues.The projects featured at SARSEF’s annual fair during this time were not only a reflection of these shifts, but also a testament to the fair’s growing role in shaping the intellectual landscape of Southern Arizona and beyond.

Angelina Maynes is a University of Arizona alum and reporter with Tucson Spotlight. Contact her at angelinamaynes@arizona.edu.

Tucson Spotlight is a community-based newsroom that provides paid opportunities for students and rising journalists in Southern Arizona. Please support our work with a paid subscription.