Digital loan costs strain Pima County Library as ebook demand soars

Libraries have to purchase each individual copy of each title they want to offer as an ebook, which come at a steep markup and are time or loan-limited.

Ebooks are rising in popularity, especially when it comes to digital loans from local libraries through apps like Libby and Hoopla.

Libby celebrated its one billionth borrowed title last year year, and readers checked out 662 million ebooks, audiobooks and digital magazines—a 30% increase over 2022.

Digital loans are popular in Pima County, too.

In the last year, there were 2,844,038 digital loans and 2,278,059 physical items checked out from Pima County’s libraries.

And while digital loans are a great deal for consumers, they’re actually quite expensive for the local libraries that lend them, and a recent ruling from the U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals has outlawed a cheaper alternative.

With libraries across the country and in Pima County facing shrinking budgets and a growing demand for their services, the ruling further limits their ability to create equity in the communities they serve.

When a library purchases a book, it can lend it out to patrons as many times as they want.

“We could have it for hundreds of checkouts until it falls apart or is no longer relevant,” Pima County Public Library Director Amber Mathewson told Tucson Spotlight.

But that’s not the case with digital books.

“With each digital copy, we have to buy the rights to it after so many circulations,” Mathewson said. “So, after 26 people have used it, we have to pay again.”

With digital books, libraries end up paying publishers multiple times for a single copy.

First, they have to subscribe to an aggregator platform like OverDrive, which comes at a cost. Aggregators also have total control over the content in their catalog, which can be removed at any time, for any reason and without input from local libraries.

Libraries also have to purchase each individual copy of each title they want to offer as an ebook, which come at a steep markup and are time or loan-limited.

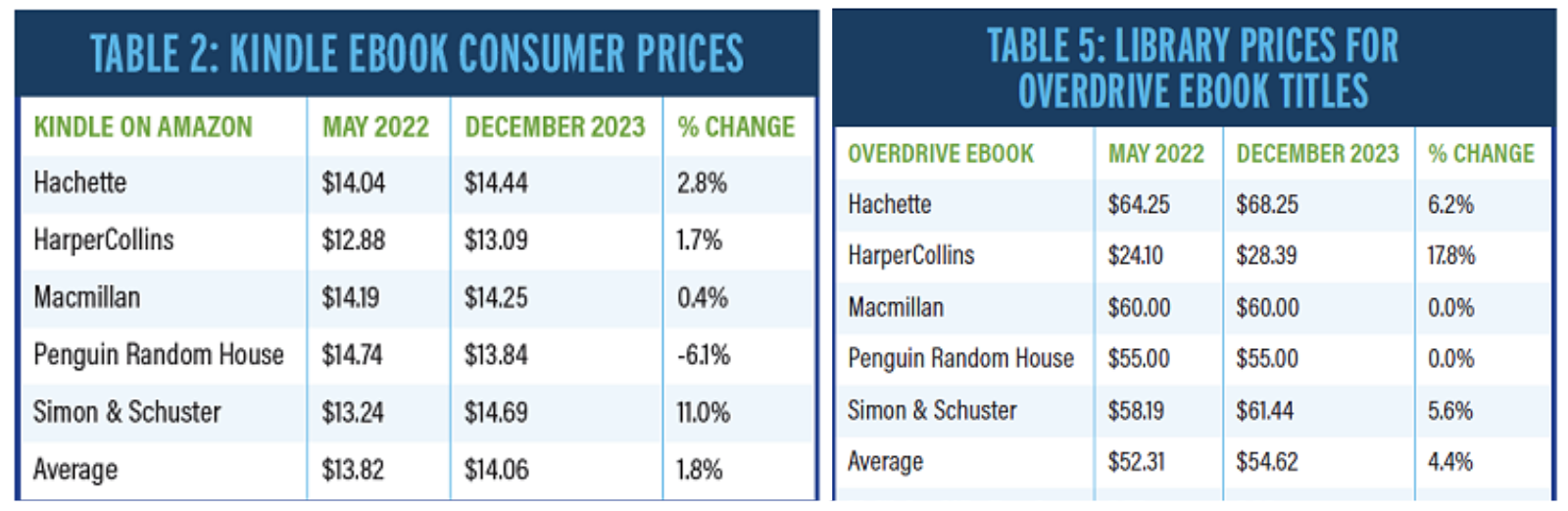

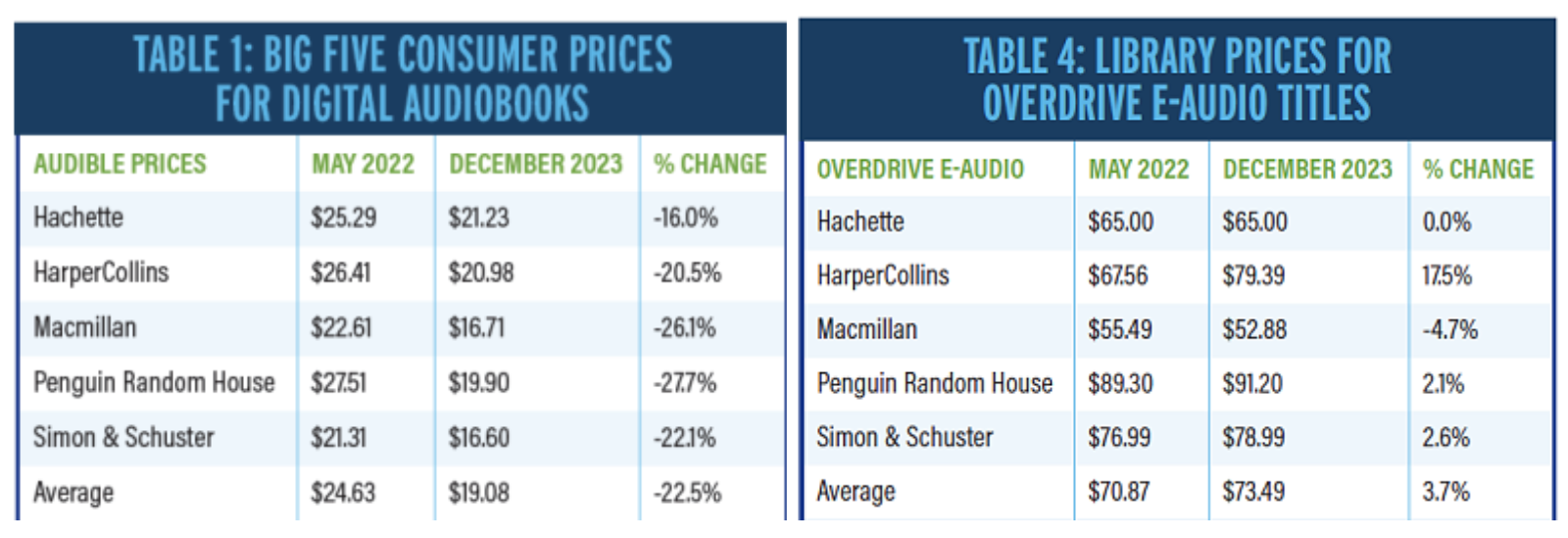

The American Library Association reports that libraries often pay publishers $55 for one copy of a popular e-book for two years, while the same ebook costs an individual consumer $15 for perpetual use.

With loan-limited books, the title essentially self-destructs after a certain number of uses (26 for books published by HarperCollins,) and the library must repurchase the same ebook at the current price if they want to keep lending it out.

Mathewson said for many years the library’s digital lending hovered at about 16% of its total checkouts, but in the four years since the pandemic, digital circulation has surpassed physical loans.

The Pima County Public Library now spends about 50% of its materials budget on digital titles, with Mathewson saying that many other libraries are now spending upwards of 60% of their materials budgets on digital titles.

There are also different fee structures for streaming videos offered through the library’s website, and in some cases, the library is charged each time someone watches a video.

“We finally had to put a limit on how many checkouts people can have,” Mathewson said. “We couldn’t keep paying for the unlimited amount of uses.”

The rise in popularity of digital loans has placed financial strain on libraries, with some turning to a solution called controlled digital lending.

Through CDL, a library scans the physical books it already has in its collection, makes secure digital copies and lends those out on a one-to-one ratio. When the digital copy is loaned, the physical copy is pulled from circulation, and when the physical copy is checked out, the digital copy is made unavailable.

The Internet Archive was an early adopter of this technique, but publishers were quick to take action against the model. In 2020, four publishers sued the Internet Archive over its CDL use, accusing it of mass copyright infringement.

The Internet Archive argued that the digitization and lending was fair use, but the trial court and court of appeals sided with publishers.

While Pima County did not have any CDL titles prior to the ruling, MIT Technology Review’s Chris Lewis says the ruling harms both libraries and consumers, by locking libraries into an “ebook ecosystem designed to extract as much money as possible while harvesting (and reselling) reader data en masse.”

“By increasing the price for access to knowledge, it puts up even more barriers between underserved communities and the American dream,” Lewis wrote.

In August, a draft proposal of a plan to close or downsize five branches of the Pima County Public Library made waves in the community when the Arizona Luminaria broke the news.

In a public report, library leadership warned of short staffing and the strain providing services to unhoused members of the community has put on the library’s ability to serve patrons.

The report said that the county would not be able to support all 27 branches with its available staff, shocking community members, who flooded the county with concerns through emails, on social media and in a September meeting.

Officials backed off on the plan and started a community engagement process, with the issue to be revisited and voted on by supervisors sometime in the spring or summer.

Until then, Mathewson said the library is focusing on being good stewards with their current funding, including their use of digital loans.

“We’re really trying to balance that and walk the line of having digital available, but also having print copies,” she said. “We’re committed to making sure that we can provide the best service to the most people with the resources that we have.”

Caitlin Schmidt is Editor and Publisher of Tucson Spotlight. Contact her at caitlin@tucsonspotlight.org.

Tucson Spotlight is a community-based newsroom that provides paid opportunities for students and rising journalists in Southern Arizona. Please support our work with a paid subscription.